Both these fingering weight 100% silk yarns were dyed with fresh Japanese Indigo leaves which I grew in my garden, then picked to make a vat, following a dye method specified on the Wild Colours website. I keep my Japanese Indigo plants well fed and watered, but the pale blue on these skeins reminds me there had been little sun to ripen the leaves in the early part of the summer. Their indigo content wasn't strong and even though I soaked all the silk in water for a whole week before dipping it in the vat, the uptake of dye isn't perfectly even.

My companion, Elinor Gotland, is something of a connoisseur where silk is concerned.

'Might as well chuck out that stuff on the left, Beaut.'

'What, isn't it real silk?'

'Oh, it's silk alright, but it's just Tussah and not even good Tussah.'

'I could never chuck out silk - as far as I'm concerned, pure silk still travels by camel, carried across the deserts from the mysterious Orient.'

'Silk is rarely pure and never simple. For a start, Tussah is made by worms that eat oak leaves and spin coarse brown cocoons that usually get dunked in bleach. After that, who knows what further horrors befell this drab collection of short, weak fibres.' Turning to the the other skein, Elinor sighed in satisfaction. 'Whereas this, my dear Fran, is Mulberry silk. From special worms fed only on mulberry leaves. They make cocoons of long, gossamer fine silk which is naturally white. On the long journey to you from the silkworms, these fibres have been carefully cleansed, tenderly unravelled and meticulously spun into glorious, gleaming yarn. Time to adjust your illusions, Beaut. Neither of these silks got here by camel train. Let's say, this Mulberry arrived by limousine and that Tussah waited 20 minutes in the rain for a bus.'

'Well, at least the Tussah took up the indigo dye better than the Mulberry. Mum bought it for a weaving project and I was planning to turn it a darker blue for her, once a bit more sunshine had built up the indigo in the plants for a better dye vat, only she got ill and died.'

'How awfully sad, such a mistaken purchase, the weaving would never have repaid her effort. A baby mouse could pull that Tussah apart. Never mind, you can make me something nice with the Mulberry.'

This single spun Tussah does indeed snap with a sharp tug, while you can pull on one strand of the plied Mulberry so hard it cuts into your hand and it still doesn't break. They say it takes a good friend to tell you an unwelcome truth, though as an ancient statesman once said, there is some self-interest behind every friendship.

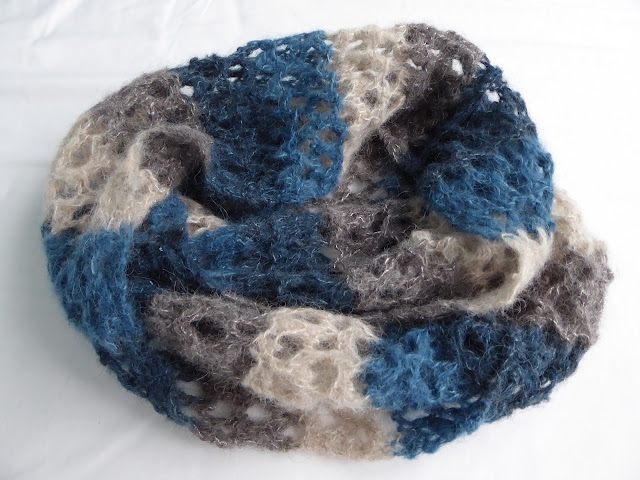

Putting both hanks of silk back in their bags and searching for another project, in my chest of stashed yarn, I found four 25g balls of Drops yarn, 77% brushed alpaca, 23% silk, - the label doesn't say what kind of silk. Originally, I bought two of the natural grey and two of the white. Early last summer, I dipped one of each into an indigo vat. The alpaca took up the indigo more strongly than the silk and I think the overdyed grey alpaca contrasts more dramatically with its silk core than the medium blue result on white alpaca does against the paler blue of the indigo uptake on the silk.

The brushed alpaca forms a cloud only loosely bound to the silk core of the yarn, which makes it very light and fluffy, though I generally expect silk to hang with great drape. I knitted it into a striped version of the Connections Cowl pattern. The original cowl, knitted in a silk/linen blend yarn, took 200m and weighed 100g, whereas this one needed a few extra pattern repeats to reach the same length and took 250m of yarn, but still only weighed 45g. Both yarns are categorised as worsted/double knitting at 9 wpi. I don't think the difference is simply grist, however it was prepared and spun, wool of the same grist as either would be unlikely to behave in the same way. Nature over nurture, a yarn's character must have much to do with its constituent fibres.

My companion, Elinor Gotland, is something of a connoisseur where silk is concerned.

'Might as well chuck out that stuff on the left, Beaut.'

'What, isn't it real silk?'

'Oh, it's silk alright, but it's just Tussah and not even good Tussah.'

'I could never chuck out silk - as far as I'm concerned, pure silk still travels by camel, carried across the deserts from the mysterious Orient.'

'Silk is rarely pure and never simple. For a start, Tussah is made by worms that eat oak leaves and spin coarse brown cocoons that usually get dunked in bleach. After that, who knows what further horrors befell this drab collection of short, weak fibres.' Turning to the the other skein, Elinor sighed in satisfaction. 'Whereas this, my dear Fran, is Mulberry silk. From special worms fed only on mulberry leaves. They make cocoons of long, gossamer fine silk which is naturally white. On the long journey to you from the silkworms, these fibres have been carefully cleansed, tenderly unravelled and meticulously spun into glorious, gleaming yarn. Time to adjust your illusions, Beaut. Neither of these silks got here by camel train. Let's say, this Mulberry arrived by limousine and that Tussah waited 20 minutes in the rain for a bus.'

'Well, at least the Tussah took up the indigo dye better than the Mulberry. Mum bought it for a weaving project and I was planning to turn it a darker blue for her, once a bit more sunshine had built up the indigo in the plants for a better dye vat, only she got ill and died.'

'How awfully sad, such a mistaken purchase, the weaving would never have repaid her effort. A baby mouse could pull that Tussah apart. Never mind, you can make me something nice with the Mulberry.'

This single spun Tussah does indeed snap with a sharp tug, while you can pull on one strand of the plied Mulberry so hard it cuts into your hand and it still doesn't break. They say it takes a good friend to tell you an unwelcome truth, though as an ancient statesman once said, there is some self-interest behind every friendship.

Putting both hanks of silk back in their bags and searching for another project, in my chest of stashed yarn, I found four 25g balls of Drops yarn, 77% brushed alpaca, 23% silk, - the label doesn't say what kind of silk. Originally, I bought two of the natural grey and two of the white. Early last summer, I dipped one of each into an indigo vat. The alpaca took up the indigo more strongly than the silk and I think the overdyed grey alpaca contrasts more dramatically with its silk core than the medium blue result on white alpaca does against the paler blue of the indigo uptake on the silk.

The brushed alpaca forms a cloud only loosely bound to the silk core of the yarn, which makes it very light and fluffy, though I generally expect silk to hang with great drape. I knitted it into a striped version of the Connections Cowl pattern. The original cowl, knitted in a silk/linen blend yarn, took 200m and weighed 100g, whereas this one needed a few extra pattern repeats to reach the same length and took 250m of yarn, but still only weighed 45g. Both yarns are categorised as worsted/double knitting at 9 wpi. I don't think the difference is simply grist, however it was prepared and spun, wool of the same grist as either would be unlikely to behave in the same way. Nature over nurture, a yarn's character must have much to do with its constituent fibres.

' Elinor, see how differently these cowls hang on me and my sister.'

'I see Pip can raise a smile with 100g of yarn around her neck. With less than half the amount of silk to carry, you look like a knackered camel. Come on, I'll put the kettle on. Reckon the old dromedary can still make it to the watering hole?'

'I see Pip can raise a smile with 100g of yarn around her neck. With less than half the amount of silk to carry, you look like a knackered camel. Come on, I'll put the kettle on. Reckon the old dromedary can still make it to the watering hole?'